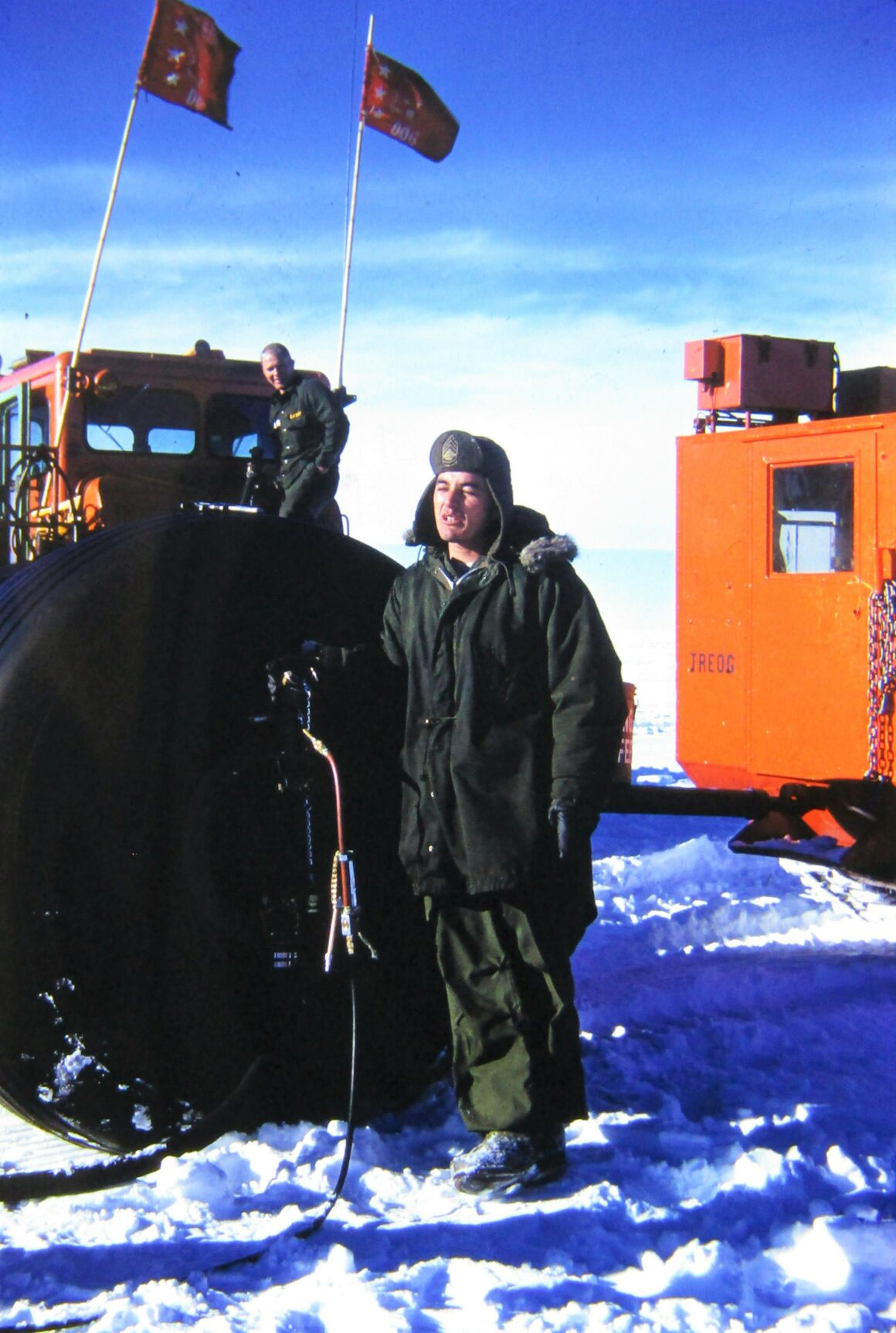

Augustin “Marty” Martinez has had more hands-on time with Overland Trains story than any one individual. He was the primary Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) in charge of the Sno-Freighter’s recovery after it caught fire and was immobilized deep in the Yukon. His documentation, slides, and personal stories of these events adds significant depth to our events understanding. Aside from his firsthand knowledge, he and his wife are just good human beings.

How Did we Meet?

On June 2, 2021, I received an email that said,

Hello;

I just stumbled upon your Overland Train website. I wish I had found it sooner than today! Thank you for keeping the history alive. Would you be interested in speaking with my husband? He was the Sergeant in charge of the recovery of the snow train that jackknifed in the Yukon. He has some photos and the Army assessment report of the MKll from 1961-62. It was called “Operation Willow Freeze”. It took place after the Willow Freeze maneuvers that year.

My husband may be the only one left from that adventure. We tried to find the crew members in Alaska a few years ago but everyone seems to have passed on. If you are interested, let me know.

The email was from Marty’s wife. As I continued reading her email, I saw that in her signature they were located in Tacoma, WA. I live in Gig Harbor, WA, making this right across the way – 20 minutes or so! When she said that her husband may be the only one left from that adventure, she was likely correct. I am not aware of anyone else alive that could tell the story that you are about to read. As I found out, Marty’s stories, documentation, and slides significantly drive the Sno-Freighter and Sno-Train history.

Marty’s Beginnings

Marty was born in Colorado, April 1932. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1950 and retired as an E-8 (First Sergeant) in August 1972. His enlistment took him to Korea, Germany, Vietnam, Fort Belvoir, Fort Eustis, Alaska, Yukon Territories, and others.

Lead Dog 60

From May to July 1960, Marty participated in the U.S. Army Transportation Corps Operation Lead Dog 60. The official report was titled, “A Traverse of North Greenland and an Aerial and Surface Exploration of Peary Land and Crowne Prince Christian Land.” Some of his slides from that maneuver are found below. You can read the original report at https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0263548.

During Lead Dog 60, large unpowered Thompson Trailers were used to haul petroleum, oil, and other liquids to support the mission. These trailers would later incorporate LeTourneau manufactured rims and Firestone 120x48x68 tires, which were used on the Overland Trains. The image below with “Martinez in front of a Thompson Trailer” used the original smooth tread Bridgestone tires and metal spoked rims.

Since 1952, the United States Army has operated annual exercises and scientific studies to expand military and civilian knowledge of the Greenland icecap and other neighboring land areas. Project Lead Dog 60 is a continuation of those studies from 1952 that includes the Department of Defense and 9 other agencies.

During this study, PR&DC at Camp Tuto, Greenland provided cached fuel support for the convoy. They also provided support in the way of spare parts, communication, and two support flights. The convoy, or swing, departed Camp Tuto on May 18, 1960. Scientists conducted geologic, geographic, and archeologic studies. The operation lasted 68 days.

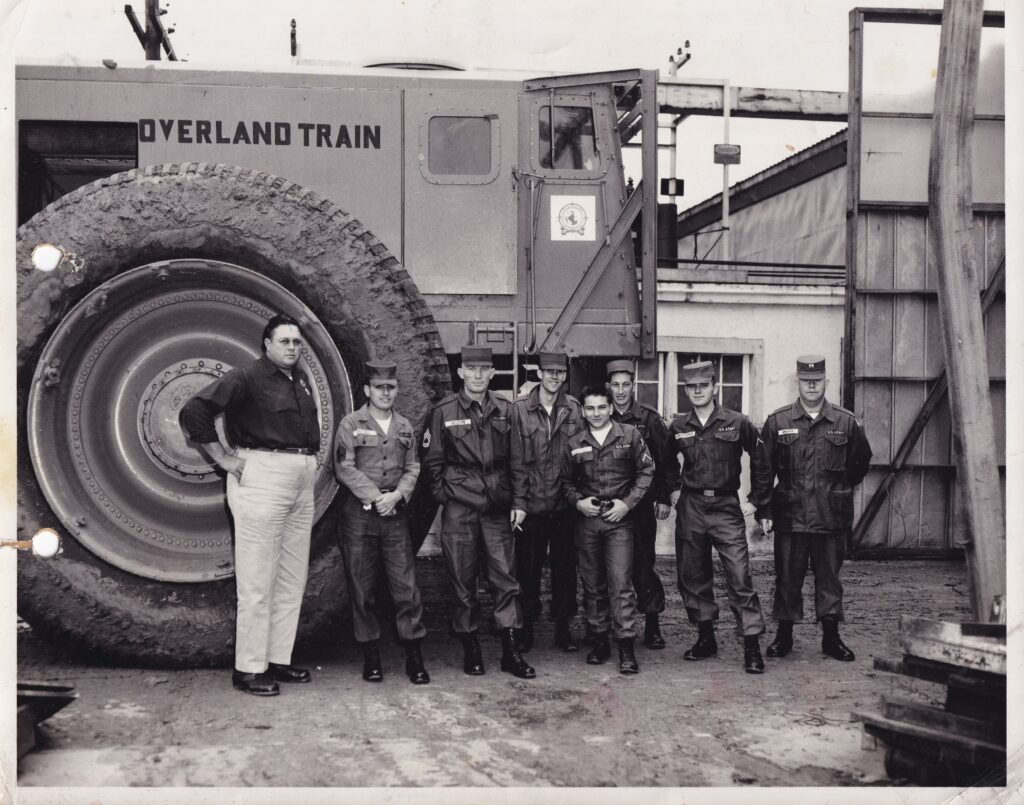

R. G. LeTourneau, Inc. Sno-Train Service Training Course

When the Sno-Train was sent back to R. G. LeTourneau, Inc. in December 1960, the Army also negotiated a contract for a service training course. Martinez and his crew attended the course to further their knowledge and understanding of the Sno-Train’s systems.

During the Sno-Train Service Training Course, the factory was building another Overland Train, the TC-497. You can read more about the TC-497 here.

Environmental Operation Willow Freeze

Operation Willow Freeze was a five phase field exercise designed to understand logistic operations were needed to support independent, disperse armed forces in Artic terrain. The exercises occurred from January 5th to March 8th, 1961. During the exercise, the Sno-Train experienced tire puncture after tire puncture. The machine had performed well and traversed hundreds of miles in the Arctic. However, the current operations took place in marshy and woody terrain in the bitter cold.

Any time that the Sno-Train would trample over small trees, they would get broken off several feet from the ground level. The snow cowl, which was installed in Camp Tuto, Greenland was used to push the snow to the sides, instead of building up in front of the Sno-Train. However, the snow cowl acted like a large bumper, breaking off these small diameter trees at about waste level.

These trees acted like spears to the relatively thin 12-ply tires. Puncture after puncture occurred until the Sno-Train was deemed unfit for continuing. The Army called on Martinez to figure out how to replace these tires on site. Martinez would replace the tires from those found on the trailer and another type of non-LeTourneau trailer called the Thompson Trailer.

Here’s an excerpt from the book “R. G. LeTourneau’s Overland Trains: a complete history.“

“The Sno-Train traveled three miles before the two passenger-side tires were punctured at the same time – front and rear. The passenger side front tire developed a puncture and subsequently tore an eight-inch gash through the entire tire. The culprit was a broken and frozen Birch tree. The passenger side rear tire also fell victim to a piece of frozen Birch and completely punctured the tire. The Sno-Train did not carry a repair kit or spare wheel assemblies – those were back at [Gulkana Support Base] GSB.

A Wagner 4-Track Transporter went back to GSB to bring tools, a replacement wheel assembly (rim and tire), and other equipment to repair the tire damage from the Birch trees. The Wagner vehicle made a second trip back to GSB to get a 6,000 pound forklift. Changing the 2,322-pound wheel assemblies was a relatively straightforward task. [Martinez] used the Sno-Train’s rear-mounted jib crane to lift the old wheel assembly away and then lift the new assembly on the hub.

This process took three hours. Changing the passenger side front tire was much more involved. The operators figured out a creative way to change the passenger front tire using a forklift, the Wagner vehicle, and a jack. The Sno-Train’s jib crane is positioned to the rear of the control car. The jib crane was unable to reach to the front of the Sno-Train, making it useless for changing out the front tires. Operators secured the 6,000-pound forklift to the rear of the Wagner vehicle with chains. Then, cables were attached to the forklift forks, which were attached to the wheel assembly. At the same time, a 20-ton jack was used to lift the Sno-Train’s axle to give clearance and remove ground tension on the tire. The procedure took eight hours to change out the wheel assemblies, with an average temperature of -20F. Unfortunately, they would find problems with the replacement wheel assemblies and have to complete the process all over again.

The Sno-Train was equipped with original equipment manufactured wheel assemblies. The clearance between the front wheels and the frame was only 3-inches, leaving just enough room for tire deflection. The replacement rims acquired from the GSB were a newly designed rim from TRADCOM that had slightly different measurements, enough to cause incompatibility with the Sno-Train’s front wheel clearances.

When these new wheel assemblies were mounted on the Sno-Train, they reduced clearance between the frame and tire to zero. Wheel assemblies were removed from one of the Sno-Train’s trailers and mounted on the front of the Sno-Train’s control cars, while the newly designed TRADCOM wheel assemblies were used on the trailer. This time, an M62 5-ton wrecker was used to help expedite the wheel assembly swaps.“

You can read more about Operation Willow Freeze here.

Recovering the Sno-Freighter

While Martinez was at Willow Freeze with the Sno-Train, he and his team was redirected to recover the Sno-Freighter. Alaska-Canadian Freightways, the owner at the time, contracted with the U.S. Army to recover the machine. The Army would provide recovery equipment, personnel, and supplies for the contingent during their efforts.

Exiting from Willow Freeze in Galkana, AK, the Sno-Train, Martinez and crew first traveled 137 miles to Fort Greely, AK for resupply and maintenance. The Sno-Train left one of its three trailers at Fort Greely, as it was not needed for recovery operations. The crew left Fort Greely on March 31, 1961.

The Sno-Train traveled east to the Yukon Territories, Canada through Tok Junction and to Dawson. From Dawson, the crew made it to Chapman Lake on April 29, 1961. A decision was made to leave one of the two trailers at the lake. It was hauling a spare tire and rim. If it was needed, a small contingent would travel back to retrieve the trailer. The crew continued through Cache Creek Valley and on to the Sno-Freighter’s location, where it had been for nearly five years.

Crew had to seal and repair the Sno-Freighter’s tires using powdered milk, which worked extremely well. A significant amount of electrical work was needed to prepare the Sno-Freighter and Sno-Train for travel. Martinez and his crew used a small generator, which was mounted on the rear of the Sno-Freighter’s control car, to provide electrical energy to release the brakes on each of the wheel motors.

Connecting the Sno-Freighter to the Sno-Train

The Sno-Train’s electrical system was connected to the Sno-Freighter to power each of the LeTourneau Electric Drives. In short, the Sno-Train’s power generation system was going to work double-time to recover the Sno-Freighter. The Overland Train convoy was largely underpowered. The Sno-Train did not have enough current to move both Overland Trains from a dead stop in the marshy ground. A bulldozer was used to pull the two trains and start the momentum.

Traveling across the melting permafrost was difficult on the machinery. There were breakdowns, electrical generator failures, and bent pushrods… The Overland Train convoy eventually made it back to more civilized terrain after many miles of rough goings. The Army’s recovery contract was terminated on July 5, 1961.

The Sno-Freighter was towed to Bear Creek, where it sat for many years. The Sno-Train was left at the Dawson airport for the winter.

Several months after leaving the Sno-Train at the Dawson airport, Martinez flew back from Fort Eustis and then drove it back to Fort Greely. The Sno-Train was eventually sold at auction to Carl “Pete” Peterson, who owned a salvage yard near the Fort. Several years later, the Sno-Train has a familiar visitor.

Visiting the Sno-Train and Sno-Freighter in Alaska

When Marty retired from the military, he worked in Tacoma, WA. He maintained an active tinkering lifestyle, often looking for obscure parts for his creations. One of his frequent salvage yards was found in Roy, WA.

One day, Marty was looking for a specific part at that Roy yard and started talking to a man named Pete. As Marty and Pete began talking, they made a connection to the Sno-Train. Pete owned the Sno-Train and had it in his Alaska based salvage yard. They stayed in touch over the years until one day Martinez traveled up north for a vist. Years after leaving the Sno-Train behind at Fort Greely, Martinez went back to Alaska, visited Pete at his salvage yard, and became reacquainted with a few old friends.

While in Alaska, Marty also had the opportunity to visit the Sno-Freighter outside of its home near Fox, AK. Inside the machine, he found a 3/8″ wrench that was likely leftover from the recovery operations. As Marty said, he likely signed for the wrench in the Army anyways; he still has that wrench today.

The Sno-Train was in Pete Peterson’s yard for many years prior to his passing. After his death, Pete’s son sold the Sno-Train on eBay – see the original listing.

While in Alaska, Marty also had the opportunity to visit the Sno-Freighter outside of its home near Fox, AK. Inside the machine, he found a 3/8″ wrench that was likely leftover from the recovery operations. As Marty said, he likely signed for the wrench in the Army anyways; he still has that wrench today.

Buy the Overland Trains Book