Nate Galbreath’s page at http://thule1954.com is being redirected to a GeoCities page with the same content at http://www.geocities.ws/nategal/. The domain and hosting was no longer active. I purchased the domain and redirected to his active site.

Nate Galbreath’s page at http://thule1954.com is being redirected to a GeoCities page with the same content at http://www.geocities.ws/nategal/. The domain and hosting was no longer active. I purchased the domain and redirected to his active site.

Writing the Overland Trains book has made me more sentimental. Conversations with individuals and their kin about the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, Alaska, and Yukon history made me realize that many of the historical artifacts and accompanying stories are being lost to children that “just don’t have the space” and degradation due to time. I will buy artifacts like the DEW Line beanie and challenge coin to preserve them for history and others to enjoy. The beanie seller said that it “Came from the estate of a gentleman stationed on the DEW line in the 70s.”

R.G. LeTourneau’s Overland Trains were not the first large rubber tires to navigate the extreme snow and ice. When Dr. Thomas C. Poulter received notification that Admiral William Byrd was planning an another scientific expedition to the Antarctic at the end of 1939, he secured $150,000 in funding to build the Snow Cruiser. Dr. Poulter designed the Snow Cruiser after he nearly died in a previous expedition with Admiral Byrd (1933-1935). Dr. Poulter imagined that research should be mobile; expeditions would be much safer and more effective than tent based stations. Construction on the Snow Cruiser began in Chicago, August of 1939. The Snow Cruiser was completed in 11 weeks. For comparison, the Sno-Freighter was built in 6 weeks. In 1939, the Byrd-Poulter Snow Cruiser landed in Antarctica.

Dr. Poulter designed the Snow Cruiser to float atop the snow and ice terrain. Similar to a few of the Overland Trains and Buggies, it had large tires, 10 foot in diameter, and two diesel engines that drove electrics generators for 4 independent electric wheels. It had a top speed of 30 miles per hour and could traverse a 35% grade.

The Snow Cruiser’s lack of terrain crossing became evident immediately after landing in Antarctica. The machine was tested in the sand, but never in the snow or ice. The construction rush never lended itself to increased testing. The slick Good Year tires spun on the snow and ice. The video below shows the Snow Cruiser being dug out of the mud after in drove into a muddy creek.

The machine never made it more than 92 miles a day. Researchers on board found out that the machine had more traction and power in reverse. They attempted to take the two spare tires and attach them to the front for driving operations in reverse. The LeTourneau Sno-Buggy would test the same dual tire configuration in Greenland 13 years later in 1954. Except, this time, they would drive forward! After a bit of tough goings, the Snow Cruiser was parked, marked with wooden stakes, and used as a stationary research camp until 1941. It was left to the elements not to be seen again until 1958, where it was briefly rediscovered only to get lost to the elements once again.

In 1963, the United States Navy icebreaker U.S.S. Edisto captured the photograph below of Little Miss America III, Byrd’s research station. You can still see the bamboo poles atop the ice in the top left of the image where is was marked in 1941. In 2005, two researchers, Ted Scambos and Clarence Novak, published a paper theorizing where the Snow Cruiser could be located (https://doi.org/10.1080/789610142). The iceberg containing Little Miss America III and the Snow Cruiser is now approximately 18km from the coast. The researchers in the 2005 paper did not have an exact location, but came to the conclusion that the Snow Cruiser sits on the ocean floor or on the land bound side of the ice. There is also some speculation that the Russians may have picked it up off of the sea floor years ago.

Tires

One of the base design problems with Dr. Poulter’s Snow Cruiser were the bald balloon tires. In 1939, tire manufacturers and the heavy equipment industry were just getting started using balloon tires. They didn’t have any traction components or tread as of yet. The tire molds that Good Year used for the Snow Cruiser tires were the same used on the Gulf Marsh Buggy. The Gulf Marsh Buggy was highly mobile in the snow and ice. The difference is that the tire loadings on the Snow Cruiser versus the Gulf Marsh Buggy differ by a factor of 5. The Gulf Marsh Buggy loading was approximately 3,500 pounds per wheel. The loading on the Snow Cruiser was approximately 17,500 pounds per wheel. Later analysis would show that a loading of around 6,000-10,000 pounds would be functional on the ice and snow.

Dr. Poulter Visits the LeTourneau Factory

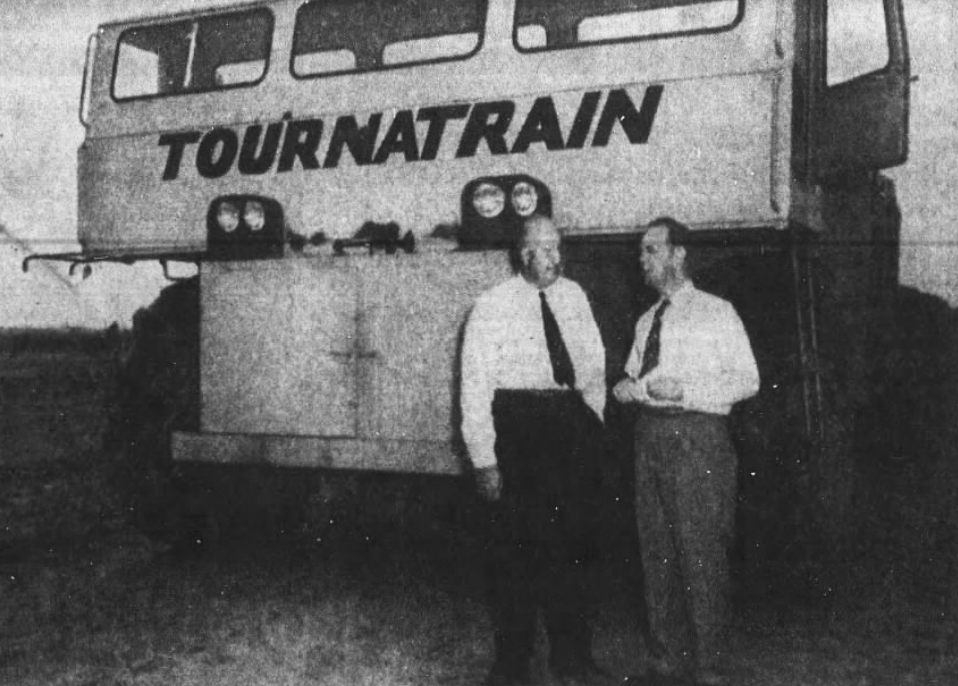

In October of 1954, Dr. Poulter visited the LeTourneau, Inc. factory in Longview, TX. In the image below, Dr. Poulter (left) is seen with R.L. LeTourneau as they inspect the VC-12 Tournatrain. Dr. Poulter stopped in at the factory, en-route to Ft. Eustis, where he was to serve as a consultant to the USAR Transportation Research and Development Command (TRADCOM).

In a different meeting, Dr. Poulter was on hand to view testing for the Sno-Buggy. He spent the day on October 14, 1954, testing the Tournatrain. Dr. Poulter was especially enthusiastic about the electric drive system used in the LeTourneau machine. The Snow Cruiser used a similar electric drive system during the 1939 expedition.

Further Reading

LeTourneau Inc.’s Sno-Buggy and Swamp-Buggy were built from the same machine; they had the same serial number. When the Sno-Buggy went to Greenland for testing, it had 2 Firestone tires per corner. LeTourneau Inc. and the U.S. Army also tested a new piece of equipment attached to the Sno-Buggy. You’ll have to wait for the book to come out to learn more! When the Sno-Buggy returned from Greenland to the Longview, TX factory, the Buggy’s tires were reduced from 8 to 4 and re-named the Swamp-Buggy.

Pine Tree Line – radar, planned 1946, handed over to Canada on 10Jan55

Mid-Canada Line or McGill Fence – 1956-1965

DEW Line – radio frequency tripwire 1957-1993, most deactivated 1988, the remaining upgraded

Green Pine Network – UHF, designed 1967, phased out in 1987

North Warning System (NWS) – radar, 1988-2025, Ratheon, AN/FPS-117 and short range AN/FPS-124 surveillance radars

Upgrade – As part of the United States Air Force new Arctic Strategy, their is a proposed upgrade occurring in 2025.

Others

The U.S. Navy also operates the Raytheon TPS-71 Relocatable Over-the-Horizon Radar(ROTHR)

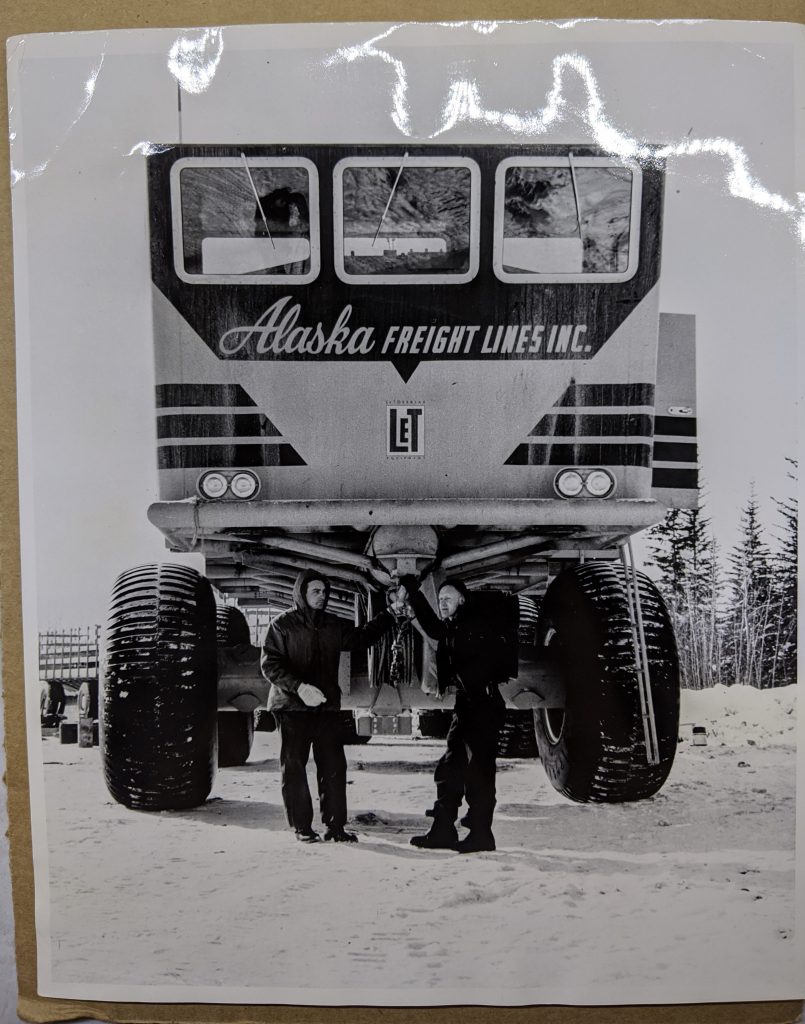

The Army’s Sno-Train is carrying a 12-ton load of an unspecified material. Even though images include dates, and sometimes locations, they can be wrong. I look for clues that could help me establish a possible location. For example, in March of 1956, the Sno-Train was shipped from the factory in Longview, TX to Houghton, MI for testing. The Sno-Train image doesn’t show a V-shaped push guard under the main cab. This addition wasn’t added until it arrived in Greenland in 1956. Images like this tell a story. You just have to know where to look.

Coots and Historic Images are two online and historic photograph sources that I use to find these amazing relic photos. When you order their images, you receive tangible photos, oftentimes with some sort of metadata on the reverse. This particular image of the Sno-Freighter was dated July 25, 1955. At this time, the Sno-Freighter should be located at the mouth of the Blow River for the winter. It wasn’t until November of 1955, that it was retrieved and the catastrophic accident occurred.

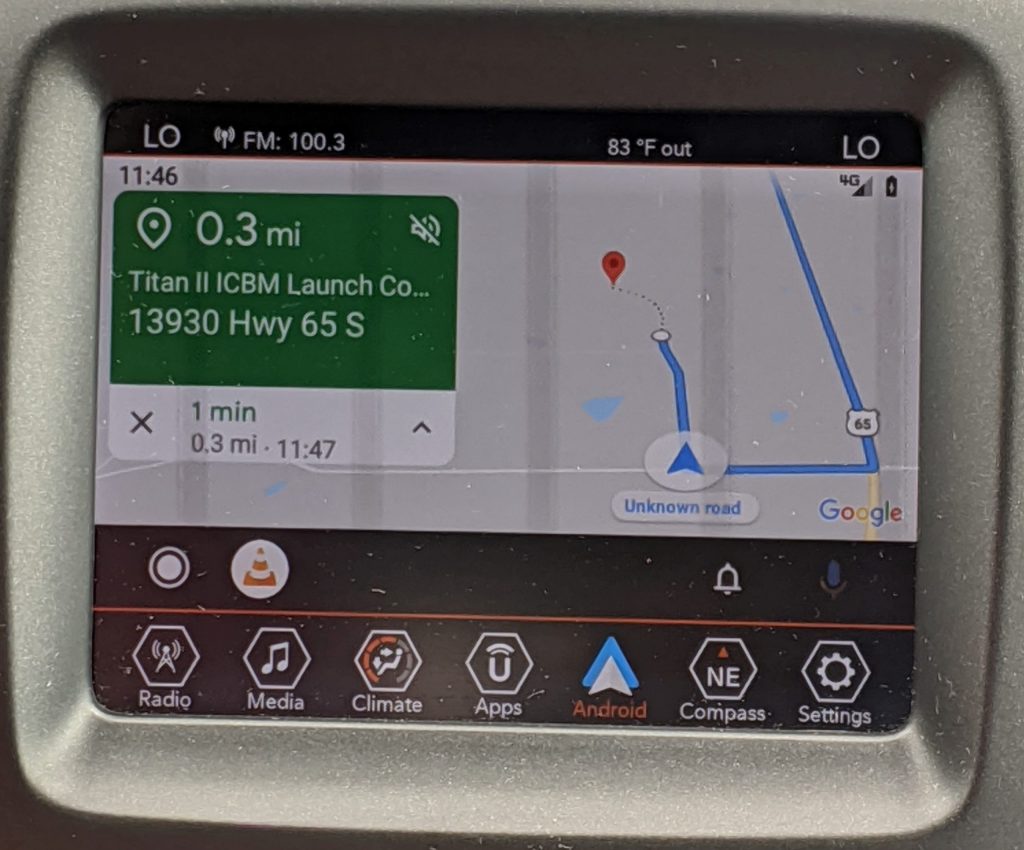

The Damascus Incident emphasized nuclear weapon safety like no other public incident to date. On September 18-19, 1980, propellant from a Titan II ICBM ignited and rocked rural Arkansas. The United States military had 5 nuclear warheads in Arkansas at the time. When a maintenance technician dropped a heavy socket down the silo, it punctured the first stage propellant tank filled with aerozine 50. The following explosion created catastrophic site damage.

I contacted the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program to see what materials they have on the site. In 2015, they provided Walks Through History tours of the site. They provided me with a site survey, or Architectural Resources Form.

Upon visiting the site on 11Sept20, I found out that the gate to access the site was locked. Based on the site maps and survey, the remaining cement pads and back-filled silo are located behind the tan barn pictured below. Unfortunately, this piece of history is not readily accessible by simply showing up. I visit Arkansas once a year. I have a year to find out how to visit the remaining site.

You can read more about the incident on Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_Damascus_Titan_missile_explosion. Visit the site on Google Maps at https://www.google.com/maps/place/Titan+II+ICBM+Launch+Complex+374-7+Site/@35.4127519,-92.3980489,492m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x87cda9b2ec84a9eb:0x15d8f2a301e71593!8m2!3d35.4141192!4d-92.3971253.

I had originally planned on a published date sometime before the end of 2020. Covid travel restrictions to Canada and an influx of new information and contacts have delayed the time frame to the second or third quarter of 2021.

Writing a book of this nature requires attention to detail, data analysis skills, and the ability to effectively organize information. As I research and collect data, it’s become apparent that I need to come up with an organization system for media. It’s important for me to keep metadata, and sources in tact, in addition to having a naming scheme that is recognizable and scriptable if necessary.

For example, the image below is now named vc12-img-L3951-dh. I chose to define my media by topic (Overland Train type), the media type (e.g. image (img), document (doc)), a number system using the original filename if applicable, and the source. In this case, I have a separate tab showing source values.